Temptations of athletes using drugs

The urge to get ahead of the competition can drive athletes to unintentionally put their health at risk.

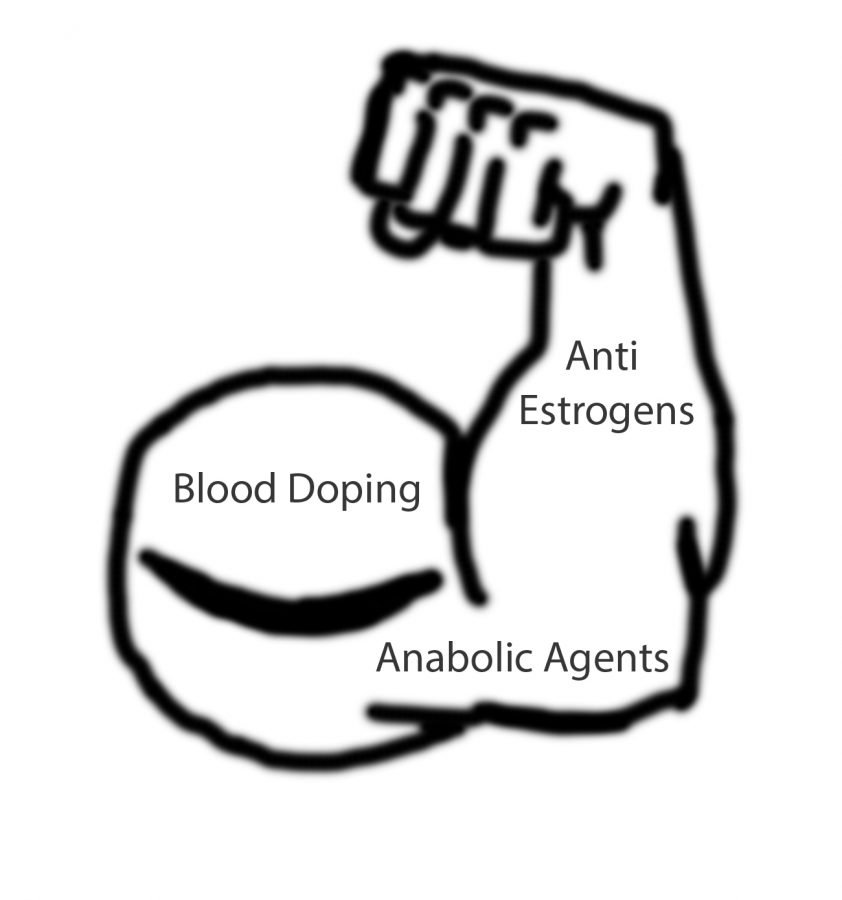

The National Collegiate Athletic Association created a list of banned drugs for the 2018-2019 season. The classifications of illegal drugs include stimulants, anabolic agents, diuretics and other masking agents, illicit drugs, peptide hormones and analogues, anti-estrogens and beta-2 agonists.

Dr. Ryan Green, assistant professor of athletic training, explained that the body is only able to handle certain amounts of stress caused by performance-enhancing drugs.

Green stated, “Regardless of the drug you put into it, when you have a performance-enhancing drug that has effects mainly on the heart and on other enzymes and glands that help maintain homeostasis, it puts everything into a system of having to work harder.”

A 2017 infographic by the National Federation of State High School Associations reported that about 20 percent of males in the age group of 18-25 years old considered using performance-enhancing drugs as the only option to become a professional athlete.

Human growth hormones, including steroids, are one form of enhancement that some athletes use.

Although the short-term effects may seem rewarding, Green explained a consequence from using HGH to increase muscle mass.

“All of a sudden, they’ve put on 30 pounds of muscle in a short period of time,” discussed Green. “If I’m a 165-pound guy and now I’m a 195-pound guy, my bones aren’t able to keep up with that demand, and my tendons might not be able to do the same thing. So, I’m putting other parts of my body at risk for damage.”

The infographic made by the NFHS showed that while 0.7 percent of NCAA male athletes reported using steroids, 7 percent of athletes reported a muscle-mass gain of more than 20 pounds in a year.

Blood doping, considered subject to restriction by the NCAA, is when an athlete injects blood into their system so that the increase in oxygen within the red blood cells attributes to a higher aerobic capacity.

Aside from its restriction, Green discussed the sanitation issues that accompany the act.

“Anytime you break the skin, there’s a chance for infection and disease to spread,” shared Green. “So, I think just from a hygiene standpoint, your skin is your natural defense mechanism for anything. Any contagious disease can get into the body when you break the skin, that protective barrier.”

Claudia Reardon and Shane Creado, professors in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Wisconsin, published a journal in the U.S. National Library of Medicine that analyzes the history and effects of different doping drugs used by athletes.

The study explained that the first step to addressing any type of drug abuse is drug prevention.

“Drug screening is used in higher-level athletics both to deter athletes from using drugs and to punish and offer opportunities for rehabilitation to those who are found to have done so,” the study stated. “Didactic education is another method aimed at prevention.”

Having worked with athletes ranging from high school to the Olympic level, Green believes that illegal drug use should not be allowed because it gives the user an unfair playing field, but he also stated that athletes should not use them, even if only during practices.

“First of all, there’s rules,” explained Green. “If you’re breaking the rules, you’re breaking the law, but secondly too, ethically and morally, you have an unfair advantage that you are hiding from competitors, hiding from oversight committees when you’re doing that.”

Your donation will support The Lion's Roar student journalists at Southeastern Louisiana University.

In addition, your contribution will allow us to cover our annual website hosting costs.

No gift is too small.

Jacob Summerville, a history and political science major, has worked at The Lion's Roar since September 2017. A native of Greenwell Springs, LA, Jacob...