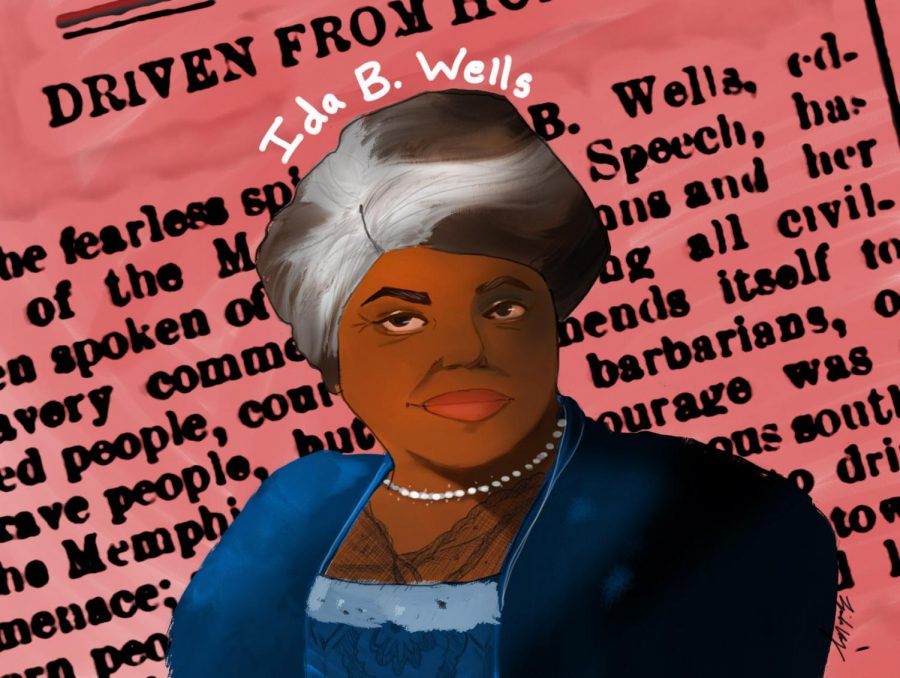

Women’s History Month Feature: The stories to tell of Ida B Wells

With Black History Month coming to a close and Women’s History Month kicking off, an African American woman worth celebrating is Ida B. Wells, who has inspired countless writers, including myself, to tell stories that give a voice to the unheard.

No matter how many times I get frustrated by writer’s block or rapid deadlines, I always keep coming back to journalism. It is what I love to do. It is what I was meant to do. With all that I hope to accomplish in my career, nothing can compare to the pioneering journalism of Ida B. Wells.

Born into slavery on July 16, 1862 in Holly Springs, Miss., Wells entered the world just prior to the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation. Her parents instilled in her the importance of education, and Wells began to attend present-day Rust College as a young teenager. At the age of 16, a yellow fever epidemic orphaned Wells, taking her parents and infant brother and leaving her to raise six other siblings alone.

Wells began teaching to keep her family together and later moved the bunch to Memphis, Tenn. Even as an educator, Wells had a natural-born investigative spirit and very low tolerance for acts of injustice.

In 1884, Wells filed a lawsuit against a Memphis train company after being manhandled and severely mistreated on a first-class train car. Wells won the case on the local level, but it was ultimately overruled in federal court.

The story made headlines in Memphis Appeal Advocate: “A Darky Damsel Obtains a Verdict for Damages Against the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad – What it Cost to Put a Colored School Teacher in a Smoking Car.”

Channeling her personal experiences and observations of life in the south, Wells began to write about the mistreatment of African Americans. Wells’ articles were published in many Black newspapers and periodicals under the moniker “Iola,” and she later became the owner of the newspaper “Memphis Free Speech,” which was eventually renamed “Free Speech and Headlight.”

In 1892, a fateful moment redirected the trajectory of her work. Wells began an anti-lynching campaign after a close friend and two of his business associates were murdered over their successful grocery store. She wrote editorials denouncing the lynchings, risking her own life in the process. Wells published “The Red Record” in 1895, her personal examination of the lynchings in America. She traveled internationally to shed light on the tragedy that gripped so many Black Americans. Openly, Wells confronted white women in the suffrage movement who chose to ignore the issue.

Despite being ostracized by various groups, Wells continued on to establish several civil rights organizations. She was also a co-founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, more commonly referred to as the NAACP. Wells may have died in 1931, but last spring, she received a posthumous Pulitzer Prize for her stories on lynching. Nine decades after her passing, Wells’ work still has an influence on our modern lives.

That is why I continue to write. That is why I keep a camera close by wherever I go. As a journalist, I am not just writing for today or tomorrow. I want to write in order to keep people alive long after their greatest tragedies. Journalism preserves the lives wrongfully taken.

Racial injustices are still widespread to this day, and my heart still breaks every so often. I struggle to find my calm and balance in being both a Black person and a journalist in today’s world. But still, I write. I write because that is what I was meant to do, and no amount of grief can take us away from what we are meant to do. Wells’ legacy is a testament to that.

I may not be the next Ida B. Wells, but I can cherish the memory of her through all that I do. By simply taking the time to understand the grievances of others and voicing out against what is wrong, you can cherish her memory too.

Your donation will support The Lion's Roar student journalists at Southeastern Louisiana University.

In addition, your contribution will allow us to cover our annual website hosting costs.

No gift is too small.

Symiah Dorsey is a communication major from Laplace and serves as Editor-in-Chief. Raised in Europe, Symiah is an avid lover of languages, traveling and...