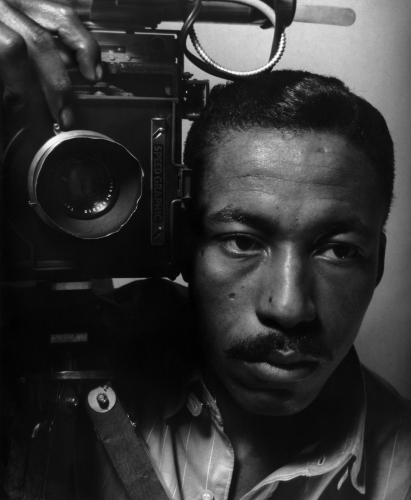

Breaking Barriers Behind the Camera: The Gordon Parks Story

Gordon Parks Foundation

In honor of Black History Month, a nation-wide celebration that spans the month of February, The Lion’s Roar will feature a series of articles written by our staff that reflect on the accomplishments of individuals who have greatly impacted African-American history.

In this moment we call life, we all seek to find our purpose and our passions. Our purpose is not only our greatest gift, but it can also become our greatest weapon.

When we are armed with our life purpose, we innately fight back against the unjust conditions society throws our way. Some of us fight back with our words, through poetry or through song. Some of us fight back with our hands, through creation or through cultivation. As for Gordon Parks, one of the greatest documentarians of the 20th century, his weapon of choice was his camera.

Born the youngest of 15 siblings in 1912, Parks’ upbringing in Fort Scott, Kan. was influenced by poverty, segregation and racial violence. His innocence was plagued by various hardships throughout his youth, such as being thrown into the Marmaton River by three white boys at age 11 and losing his mother at age 14.

Parks worked a multitude of odd jobs as a young man, and little did he know, waiting tables on a train would lead him to his life’s purpose. While on the job, Parks came across magazine images of Depression-era migrant workers. It was then that Parks decided to save enough money for a camera of his own. This $7.50 Seattle pawnshop camera was the beginning of his culture-defining career.

With no experience and very limited resources, Parks embraced a self-taught journey into photography. His undeniable talent landed him his first job shooting fashion for Madeline Murphy. Parks later became the first Black photographer to work for the Farm Security Administration, the same administration that produced the magazine images he was first inspired by.

Parks was also a freelance photographer for Glamour and Ebony around this time and later went on to be the first African American to photograph for Vogue and Life Magazine. His accomplishments were significant within themselves, but it was even more awe-inspiring that he achieved this level of success in a pre-civil rights era.

In 1948, Parks’ photo essay on the life of a Harlem gang leader achieved widespread recognition and acclaim. Parks covered a variety of social topics, from poverty and racism to arts and entertainment.

Parks remained at Life Magazine for two decades, where his photographs continuously infiltrated the racial barriers surrounding him. He captured photographs of historical icons such as Muhammad Ali and Malcom X, and he also captured photographs of ordinary, everyday people. His camera did not discriminate, and that is what truly made his work stand out.

Parks didn’t only capture the rallies, demonstrations and protests; he captured the photo of a Black girl staring into a store with only white dolls. He captured the photo of a family ordering ice cream from the “colored” entrance. His photographs often displayed white and Black children playing together because to them, color really did not matter.

What made his photography so sensational is that it showed life as it was. There was nothing to glamorize; it was raw and authentic. He showed the impact of ignorance on the innocent. Parks’ photographs also helped rally support for the awakening civil rights movement, through which his documentation defined an entire generation.

Parks was a creative visionary whose talents also extended beyond his love for photography. He is also known for his works in literature, musical composition and filmmaking. In 1969, Parks became the first African American to write and direct a major Hollywood studio feature film, “The Learning Tree.” As the Gordon Parks Foundation describes him, Parks was a modern-day renaissance man.

Parks will forever be acknowledged as one of the most groundbreaking documentary photographers of all time. His life was certainly not one without struggle, but it was through his hardships that he found his purpose.

As Gordon Parks once said, “I saw that the camera could be a weapon against poverty, against racism, against all sorts of social wrongs. I knew at that point I had to have a camera.”

So now I ask you, what is your weapon?

Your donation will support The Lion's Roar student journalists at Southeastern Louisiana University.

In addition, your contribution will allow us to cover our annual website hosting costs.

No gift is too small.

Symiah Dorsey is a communication major from Laplace and serves as Editor-in-Chief. Raised in Europe, Symiah is an avid lover of languages, traveling and...