At some Japanese schools, what may appear chaotic could be botaoshi, a game about knocking down poles, highlighting team coordination.

“That game involved almost all aspects of athletic ability,” said Dr. Sanichiro Yoshida, professor of physics. “Speed, strength and coordination is very important. It’s a good sport, so you cannot win by having one very strong guy. That’s a part of the reason why the military wanted to adapt that sport for the better coordination, better teamwork.”

The goal of botaoshi may resemble capture the flag with over 100 players trying to topple the opponent’s pole while protecting their own. The length of play for each match can vary from 90 seconds to two minutes, and the poles can stand between 10 to 16 feet tall. A win is considered successfully lifting the pole at 30 degrees or lowering the tip to below 140 centimeters from the ground.

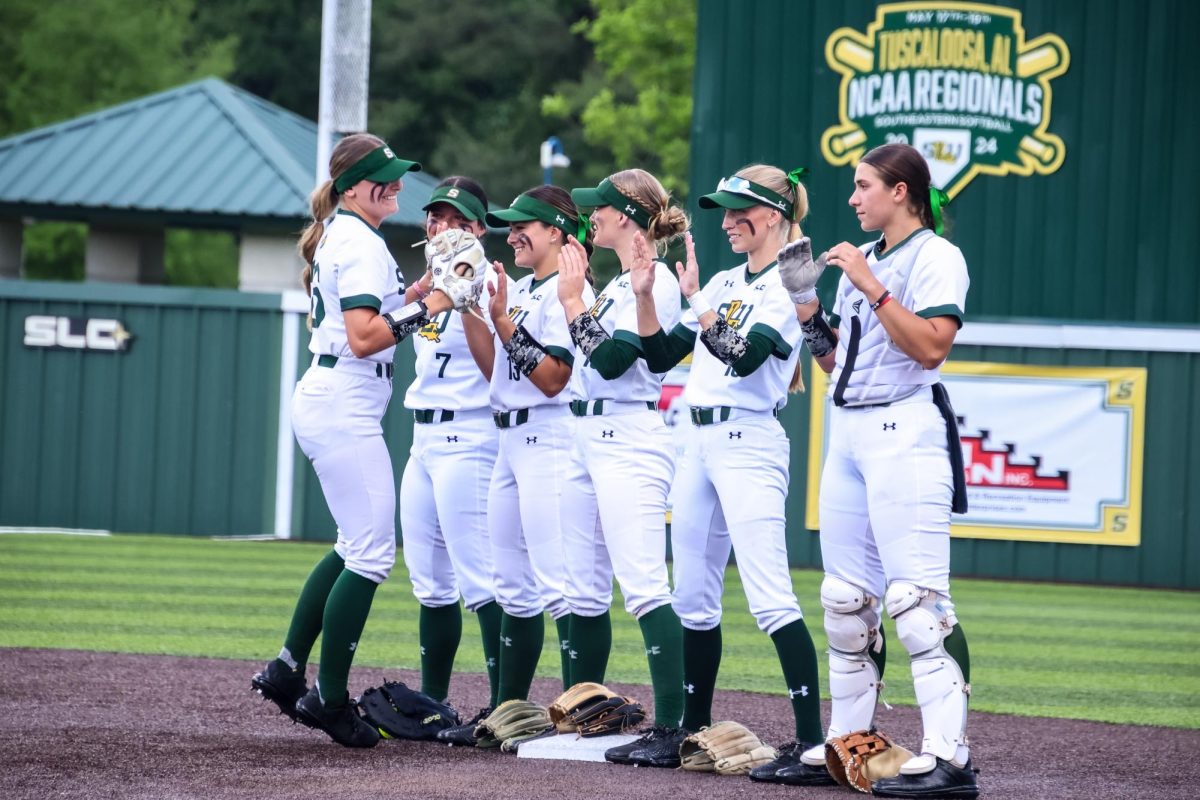

Each team consists of attackers and defenders. Within these two groups there may be subdivisions. Defenders may form concentric circles around the pole with another defender perched on top of the pole. Attackers may divide into separate groups or waves aiming to get past the defenders.

Although Yoshida has not played the game, he believes it can serve to build team synergy.

“Nowadays, many kids have lost that sort of mentality,” stated Yoshida. “They do not necessarily help each other to work together. This teamwork is a little different from teamwork in soccer and other team sports. It’s more literally help each other like a scrum in rugby.”

While the origin of the game is unknown, some hypothesize that it derived from military training in the 1940s. Today, the game is played annually at the National Defense Academy of Japan. At Kaisei Gakuen, a school in Japan, the sport has been a part of its sports festival since 1929.

“I think it came from military training,” shared Yoshida. “Now, only few high schools have the kids do the sport. Number one, it’s kinda dangerous, and second of all, it reminds them a little of the bad history of World War II, so I do not think personally the game is very popular in Japan.”

The possible militaristic history of the sport may explain botaoshi’s lack of popularity in modern Japan.

After World War II, Japan’s constitution was written to include Article 9, which forbade the formation of a traditional military. Efforts from Shinzo Abe, prime minister of Japan, to revise the article met resistance. According to the New York Times article “A Pacifist Japan Starts to Embrace the Military” by Motoko Rich, polls showed that half or more respondents disagreed with such efforts. The passage of security laws allowing Japan’s military to participate in overseas combat missions were opposed by thousands of protestors taking to the streets of Tokyo.

“The point is Japanese country was completely governed by the military, so there was no freedom,” explained Yoshida. “They had to follow whatever the military people say.”

Besides history, safety may introduce another concern. With little protection and over 100 players, injuries are common. According to “The Organized Chaos of Botaoshi, Japan’s Wildest Game” by Ken Belson, a writer for the New York Times, school records at Kaisei Gakuen showed a 52 percent increase in injuries from 2005 to 2016. Though safety precautions were implemented such as shortening game time, botaoshi retains its share of injuries.

Considering the dangerous nature of the sport, botaoshi may not expand beyond the few schools that continue the tradition.

“The problem is you go on top of other people, and that part is very dangerous, so I don’t think the U.S. would have adapted that kind of dangerous sport at least for education purposes,” said Yoshida.