Imagine: at 18, the death of three young boys has been placed at your feet. Gone are the days of high school, Stephen King novels and Metallica t-shirts; all that remains is a reputation in shambles and the fight to take back your life.

This was Damien Echols’ life for 18 years as he sat on death row in the Varner Supermax Unit in Arkansas. Echols, alongside his friends Jason Baldwin and Jessie Misskelley, were convicted of murdering three children in 1993. The trio was collectively dubbed the West Memphis Three.

Misskelley, who at the time was 16 and had an intellectual disability, gave a confession implicating himself, Echols and Baldwin after 12 hours of interrogation without a lawyer or his parents.

Prosecutors didn’t have DNA evidence to link the three to the crime scene and Echols provided an alibi, claiming he was with his family making phone calls during the night of the murder. Instead, prosecutors appealed to the jury via the Satanic panic of the ‘80s and ‘90s, claiming the three ritually sacrificed the young boys.

“The local media had run so many stories about Satanic orgies and human sacrifices that by the time we walked into that courtroom, the jury saw the trial as nothing more than a formality. It was over before we even walked in,” Echols said in 2012.

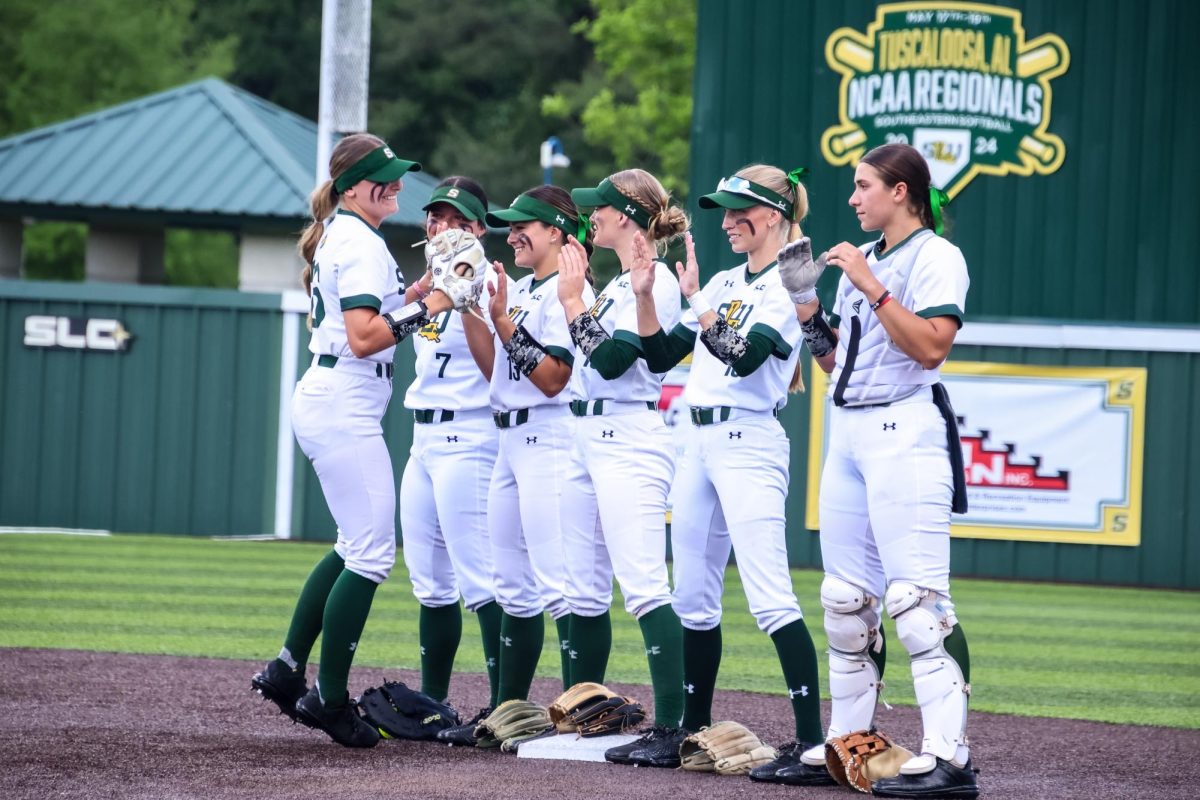

Now out of prison for 13 years, Echols and his wife, Lorri Davis, continue to spread the message of their story and work to raise awareness for the fight for exoneration. On Wednesday, March 6, SLU assistant professor of creative writing and writer-in-residence David Armand interviewed Echols and Davis in the Pottle Auditorium.

Students and faculty gathered to learn more about Echols’ jarring experience and show support for the ongoing fight to prove his innocence.

Echols discussed his experiences on death row, coping strategies, feelings after being released from prison, writing and life after release. In addition to writing spiritual books and several autobiographies, he has appeared in documentaries and hosted a podcast.

Echols shared how he began to receive support for his innocence from the public after the documentary “Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills” was released in 1996. Echols self-published his memoir, “Life After Death,” in 2008. The support and funding for Echols’ case grew.

In 2012, Davis and Echols collaborated to produce the “West of Memphis” documentary, which gave the public a deeper look into Echols’ experience.

“Everything that led to me getting out of prison, everything, was a link in a chain that led to me sitting here right now,” Echols said. “If you took one person, or event, I would be dead. Every single one of these people served an instrumental part of me sitting here now.”

Davis shed light on Echols’ situation and their connection as partners, which has remained strong throughout the years. She began reaching out to Echols while he was still in prison, sending and receiving over 5,000 letters over the course of their relationship while he was incarcerated.

“It’s pain that makes you stronger. The misery of that situation forced us to find those deeper connections,” Echols said.

The couple remained strong by strengthening their connection through phone calls, watching or listening to the same program at the same time, and even catching the moon’s reflection during a full moon, which Echols affectionately refers to as “moon water.”

Echols shared that Davis’ dedication to his release opened “impossible” doors and introduced new people to the case. They caught the attention of many celebrities who wanted to help with the case. Johnny Depp donated to the cause and became friends with Davis and Echols; they still talk to this day. Pearl Jam also helped by holding a concert in the West Memphis Three’s name and donating all the proceeds to them.

Now, almost 30 years later, Echols and Davis continue to fight for his exoneration. With the help of new DNA technology, Davis said she is hopeful the evidence will prove Echols’ innocence.

Armand said he has always felt connected to Echols’ story.

“I have been following Echols’ story for 25 years. Like him, I grew up poor out in the country. Everyone thought I had a strange way of dressing because I had long, dyed hair and piercings and was often the target of bullying from teachers, other kids and even the police on occasion. Even though what happened to Damien was an extreme example, it always frightened me to think about how something like that could have happened to me back then. It still scares me to this day.” Armand said.

The couple currently lives in New Orleans, where they live life to the fullest every day.

“Our lives are really good and we are grateful. To be able to be happy, healthy and thriving, sitting here is amazing,” Davis shared.

You can continue following Echols’ journey through his podcast on Apple Music, his patreon and social media. A petition is available on the Innocence Project website for anyone who would like to support the ongoing fight for exoneration.

Joyce Shortridge • Feb 3, 2025 at 11:21 pm

I have followed this case for many years. I’m glad they’re all out and doing well. My only regret for them is not being able to sue the state. At least that money would have helped them start a life. I’m all for the innocence project and am so happy when people get released. Must be hell sitting in a small room when you’re innocent. God bless them